Understanding the ACL: A Comprehensive Guide

by Nick Tan - Physiotherapist, Strength Clinic Academy

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is a key structure in the knee, crucial for its stability and function. Whether you're an athlete, a healthcare professional, or someone recovering from an ACL injury, understanding this ligament's intricacies can help in both prevention and recovery.

Anatomy of the ACL

The ACL is not just a simple ligament; it comprises two bundles, the Anteromedial (AM) and the Posterolateral (PL) bundles, each responding differently to knee movements. The AM bundle tightens during knee flexion, while the PL bundle does so during extension. This complex behaviour underscores the need for precision in ACL reconstruction to restore natural knee mechanics.

Function of the ACL

The primary role of the ACL is to provide anteroposterior and rotary stability to the knee. It resists anterior tibial translation and rotational loads, essential for dynamic movements. This stability is critical for athletes who engage in pivoting, jumping, and cutting activities.

Mechanism of ACL Injury

Injuries to the ACL can occur due to direct impact or, more commonly, non-contact mechanisms like sudden deceleration, pivoting, or awkward landings. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for both prevention and designing effective rehabilitation programs.

Types of ACL Tears

ACL injuries can vary significantly, from partial tears to complete ruptures, and are classified based on the amount of ligament tissue remaining attached to the femur. This classification helps in deciding the best treatment approach.

Surgical Considerations: Graft Types

When surgery becomes necessary, the selection of graft for reconstruction holds significant importance. Options encompass autografts, derived directly from the patient's body, allografts, sourced from donor tissue, and synthetic grafts. Each type has its advantages, considerations, and implications for rehabilitation .

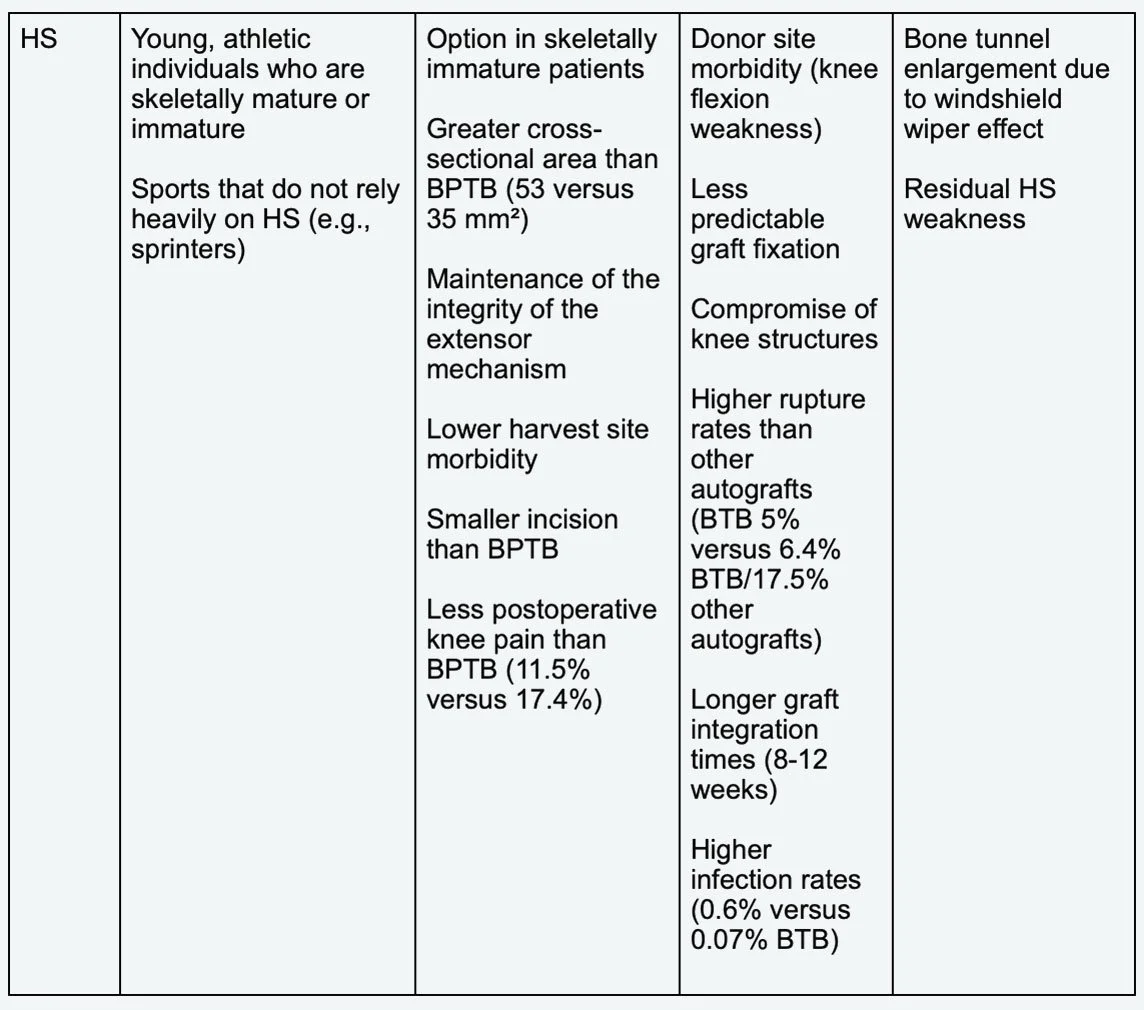

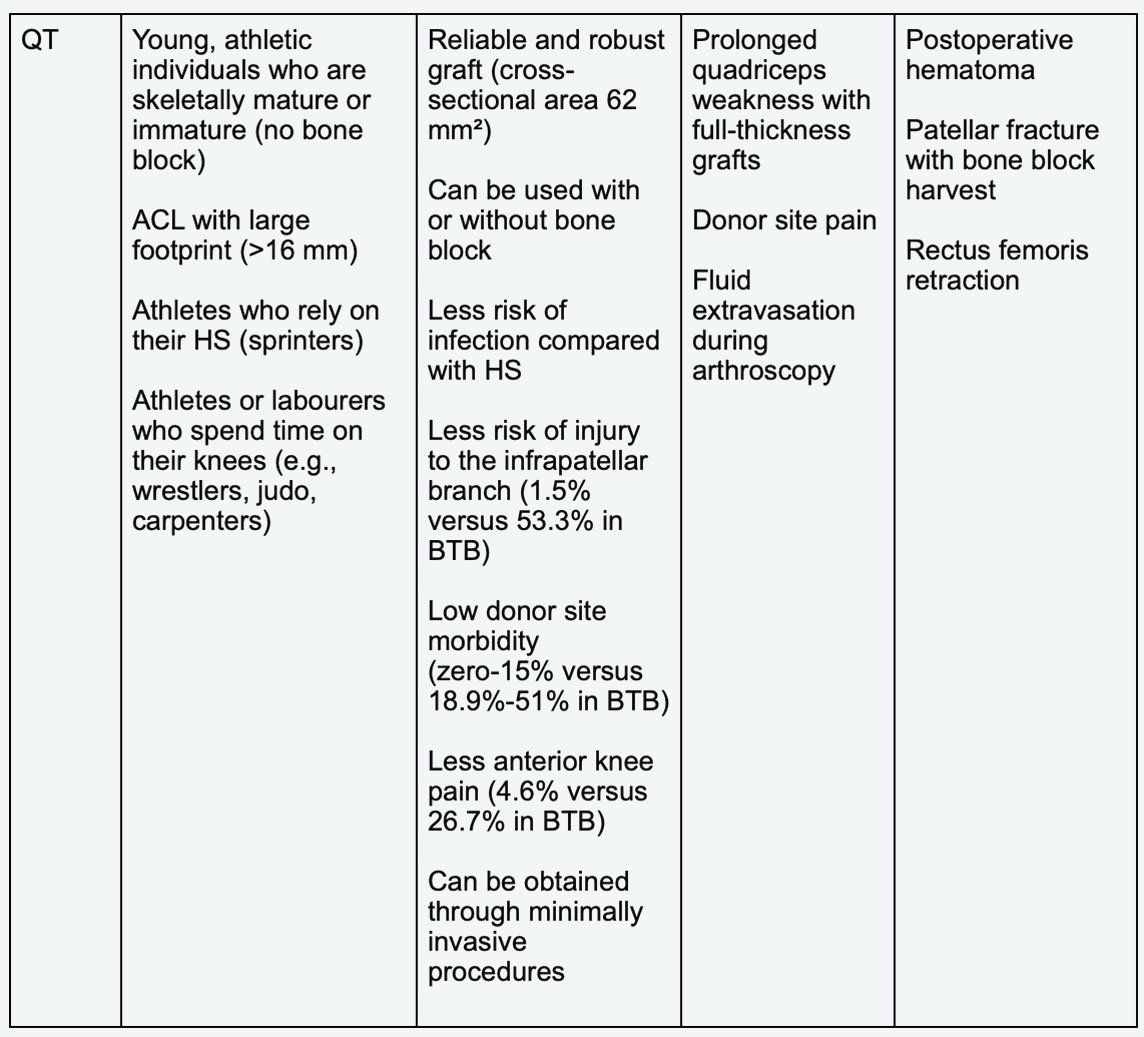

Autografts: Often preferred for younger, active individuals, options include the patellar tendon, hamstring, and quadriceps tendon. Each has its own set of advantages and potential complications, such as donor site morbidity or varying integration times.

Allografts: Suitable for older patients or those with multiple knee ligament injuries. These grafts boast shorter surgical durations and eliminate risks associated with donor site morbidity. However, they raise concerns regarding potential disease transmission and increased failure rates among younger, more active demographics.

Synthetic Grafts: These are employed to enhance the healing process of an injured ACL, rather than serving as a standalone replacement. The latest generations, like the Ligament Augmentation Reconstruction System (LARS), are designed to resist elongation and minimise wear debris. For further information on the LARS, please visit: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Ligament_Augmentation_and_Reconstruction_System_(LARS)

Advantages and Disadvantages of Graft Types

Selecting the appropriate graft involves a nuanced decision-making process that takes into account factors such as the patient's age, level of activity, and personal preferences. Each graft type has its own set of advantages and challenges, impacting the surgery's outcome and the patient's recovery.

In the surgical considerations for ACL reconstruction, the tensile strength of grafts and their advantages and disadvantages are pivotal factors. Here's a breakdown based on your documents:

Tensile Strength of Tissues:

ACL = anterior cruciate ligament, BPTB = bone–patellar tendon–bone, HS = hamstring, QT = quadriceps tendon

(Table from Buerba, Boden & Lesniak, 2021)

ACL = anterior cruciate ligament, BPTB = bone–patellar tendon–bone, HS = hamstring, QT = quadriceps tendon

(Table from Buerba, Boden & Lesniak, 2021)

ACL Healing Phases

Early Graft Healing Phase (0 - 4 Weeks After Surgery)

The objective tensile strength of most grafts is typically greater than that of an ACL. Tensile strength refers to the amount of pressure something can withstand before breaking. As a result, immediately following surgery, the graft is usually stronger than the original ACL.

Upon placement inside the body, the graft initially lacks connections to any blood vessels. Blood vessels are essential for delivering nutrients to cells, sustaining their vitality. Consequently, some cells within the graft may perish, resulting in a reduction in cell density and strength.

Proliferation phase (4 - 12 Weeks After Surgery)

The presence of dead cells prompts the body to respond by releasing growth factors, initiating various reactions. These growth factors stimulate the formation of blood vessels to nourish the ACL graft and generate new cells to replenish those lost. This process is so efficient that the body often generates an excess of blood vessels and cells. Furthermore, the new cells exhibit a random organisation on the graft.

During this phase, the graft tends to be weaker than the original ACL, reaching its lowest strength typically 6 to 8 weeks after surgery due to the ongoing changes. Consequently, engaging in sports activities immediately after ACL reconstruction surgery is considered unsafe.

Ligamentization phase (>12 Weeks After Surgery)

The graft now begins to remodel itself, which means changing the way it looks, to more closely resemble the original ACL. During remodelling, the excess blood vessels and cells are removed, and the graft starts to arrange its cells in a more organised manner. This remodelling continues to occur years after an ACL reconstruction surgery, and has no definitive endpoint.

The graft undergoes a strengthening process during this phase, facilitated by the remodelling process. Approximately one year after surgery, it regains nearly the same strength as the original ACL.

It's crucial to note that every study conducted has consistently demonstrated that a reconstructed ACL never fully attains the same biological or mechanical properties as the original ACL. Consequently, while ACL reconstruction surgery can restore the knee to a state very close to perfect health, it will never quite reach the same level of health as before the initial injury.

Conclusion

The ACL is a complex structure, and its injuries require careful consideration of various factors, including the type of graft for reconstruction. A comprehensive understanding of the anatomy, function, and advantages and disadvantages of different graft types empowers both patients and healthcare providers to make informed decisions, leading to optimal outcomes.

References:

DiFelice, G.S., Villegas, C. and Taylor, S., 2015. Anterior cruciate ligament preservation: early results of a novel arthroscopic technique for suture anchor primary anterior cruciate ligament repair. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery, 31(11), pp.2162-2171.

Steckel, H., Starman, J.S., Baums, M.H., Klinger, H.M., Schultz, W. and Fu, F.H., 2007. Anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament double bundle structure: a macroscopic evaluation. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 17(4), pp.387-392.

Buerba, R.A., Boden, S.A. and Lesniak, B., 2021. Graft selection in contemporary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. JAAOS Global Research & Reviews, 5(10).